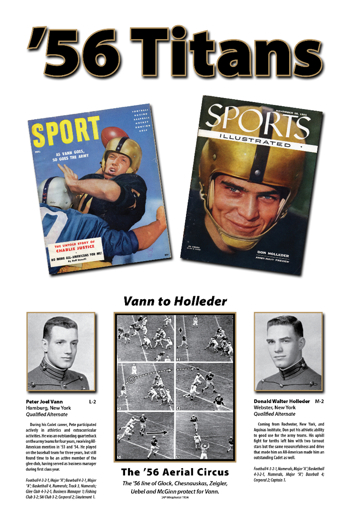

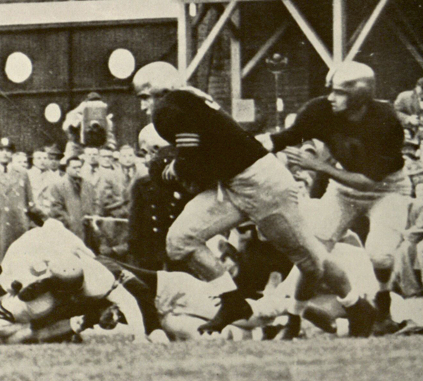

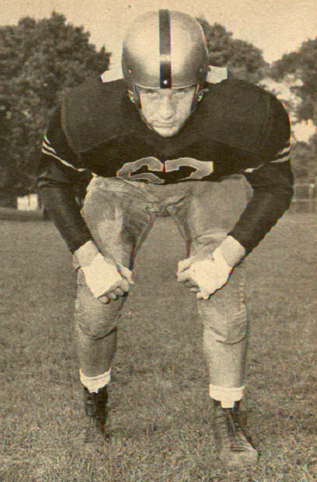

Glenn Davis in 1944 -- He played Fullback until Doc Blanchard arrived

The Webster's dictionary definition of a gentleman barely does justice to Glenn Davis. Ask Joe Shelton '44, a Firstie in Glenn's company when Glenn was a Plebe. Ask --- ---, '50, a Plebe who went on calls to Glenn's room when Glenn was a Firstie and was perhaps the most celebrated athlete in America. Ask Joe Steffy '49, Glenn's Classmate and Outland Trophy Winner. Each gives the same response when asked about Glenn: a very fine person, a gentleman.

Glenn Davis: a gentleman in the tradition of the 19th century. A genleman as Robert E Lee was a gentleman.

Glenn Davis:

"The Real Touchdown Twin"

by David Pietrusza

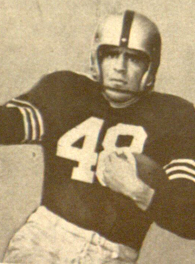

Despite being dubbed the "Touchdown Twins," Army's Glenn Davis and Doc Blanchard were not identical physical specimens. Doc Blanchard, at 6'0" and 205 pounds, was by far the bigger of the two football legends. The 5'9", 170 pound Davis, however, may have been the better natural athlete.

At the Point Davis lettered not only in football but in baseball, basketball and track. And he did not just letter. On the diamond the center fielder's arm was described as "whiplike," and he was good enough to earn Branch Rickey's comment that he could fetch a $75,000 bonus. Coming from a man with a reputation for tossing dollars around like man-hole covers, that was high praise indeed.

Even in his full football uniform Glenn Davis could flat out run, covering 100 yards in less than ten seconds Perhaps most impressive though was his performance on the "Master of the Sword" test the Military Academy devised to test the athletic prowess of future officers. Out of a possible 1,000 points on such diverse events as a 300-yard-run, dodge run, vertical jump, parallel bar dips, softball throw, sit-ups, chin-ups, and the standing broad jump, the average cadet scored 540. Davis posted a 926.5 mark, the all-time record.

While Davis was not, however, Doc Blanchard's physical twin, he was his brother Ralph's twin. Ralph was named for their father, a southern California bank manager, but it was Glenn who was always known as "Junior." Why? He was born ninety minutes after his "older" brother.

The Davis twins were nearly inseparable. They double-dated together, played harmless juvenile pranks together, and planned on attending USC together. But instead Congressman Jerry Voorhis (later defeated for re-election by a young war veteran named Richard Nixon) offered Glenn a berth at West Point. Glenn said yes but only if brother Ralph could come along.

No problem, said the Army, bring him along.

Glenn Davis had already distinguished himself as an athlete, being a four-letter man in high school and winning the Knute Rockne trophy as Southern California's outstanding schoolboy track star. In football he scored 263 points his senior year.

Davis debuted for Army during the 1943 season, running for eight TDs and passed for four more. West Point, which recently had been a football laughingstock, finished with a respectable 7-2-1 mark. It was a decent start for both Davis and his team, but it hardly gave any hint of the true greatness to come.

Football, however, was not the only thing on Davis' mind in 1943 - or maybe it was. Even though he rose at four each morning to cram in his studies, he still failed math and was in the parlance of the Academy "found" deficient. That meant he was kindly asked to leave the Academy that December to study even harder for re-admission.

Davis succeeded, returning to West Point the next fall but having to repeat his plebe year. That had its benefits. During World War II West Point was graduating classes in three years rather than four. Davis' lack of numerical expertise gave him another year on the gridiron - and ultimately the Heisman Trophy.

In 1944 Davis came into his own, leading the nation with an average of 11.5 yards per carry and in total scoring with 120 total points. Blanchard and Davis, "Mr. Inside and Mr. Outside," paced Army to an undefeated and untied season--it's first since 1916. The Black Knights scored a fearsome 504 points, 56 per game, second only to 1904 Michigan's 58.9. Army rightfully earned the Lambert Trophy, the Williams Trophy, and the Williamson Plaque.

Davis secured the Maxwell Trophy, the Walter Camp Trophy, and the Helm Foundation Award, but finished second to Ohio State's Les Horvath for the Heisman.

Speed was his forte, but it was hardly the only weapon in his arsenal. "He also possessed," Bob Carroll, the founder of the Professional Football Researcher's Association (PFRA), noted, "a devastating change of pace, a powerful leg drive, and a strong stiff arm."

Despite his natural ability the grind occasionally wore on Davis. Football required an hour and a half of grueling practice each day -in addition to the three hours of physical education required weekly of each cadet. And, of course, there was the obligation of academics and the specter of another failed math course. "I never used to think about taking a daytime nap," Davis admitted, "Now I get sleepy every time I see a sofa."

Army went on to another perfect season in 1945 and at Yankee Stadium defeated Navy for the national championship. Davis's 49-yard touchdown helped.

For the year Davis scored 108 points and led the nation with 11.5 yards per carry. Such a performance inspired the great Grantland Rice to write in November 1945: "Davis is not only one of the fastest backs that ever lugged a football on any field at any time, but he is also a strong running back who isn't easy to bring down."

And those who actually had to face him were even more impressed. "Every time Davis touched the ball," said Columbia's Gene Rossides, "it would be like an electric current going through the defending team."

Yet, it was Doc Blanchard, who led the nation in total scoring and captured the 1945 Heisman. Still when Blanchard accepted his trophy in January 1946, he told the audience: "I'd have voted for Glenn Davis."

All eyes were on Army's squad as it began its 1946 season. Both Blanchard and Davis returned for another season. Their teammates elected the "Touchdown Twins" as the first co-captains in Army football history, and they graced the cover of Life magazine.

That was the good news. Just about every other indicator was bad. First and foremost, the nation's civilian schools now benefitted from demobilization. West Point and Annapolis would no longer have their pick of athletic talent. the competition was getting equalized.

Secondly, after the some acrimonious public wrangling team lost one of its stars, Thomas "Shorty" McWilliams, who was allowed to resign from the Academy.

And against Villanova in the season's first game, Doc Blanchard hurt his knee and was never again at peak form. Davis had to pick up the slack. Perhaps his greatest moment came against Michigan when he rushed for 105 yards and caught seven passes for an additional 159 yards. Beyond that, he intercepted two passes and even threw a pass for a another touchdown.

Legendary Army coach Earl "Red" Blaik praised him as "the best player I have seen, anywhere, any time."

Despite increased competition and Blanchard's ills, 1946 Army squad still remained undefeated; the only blot on its record being a scoreless tie against Notre Dame, which dethroned the Black Knights as national champions.

Red Blaik had no apologies and ranked his 1946 Black Knights as superior than either the 1944 or the 1945 teams. "I reserve the warmest affection and the greatest respect for the 1946 team," he once wrote, " which, in the face of adversities, playing the best of college opposition, completely and thoroughly demonstrated its right to be classed as great." Much as Davis had placed second in 1944 and 1945 for the Heisman, Blaik had come in second for Coach of the Year honors both seasons. In 1946 he captured the award.

And Glenn Davis finally won his Heisman. The glory was now his. Also bestowed on him were the Maxwell Trophy, the Walter Camp Trophy, and the Associated Press designation of Male Athlete of the Year. He might have also garnered the Sullivan Trophy --- but in an administrative snafu his name had been left off the ballot

The Heisman vote:

Player School Total

1 Glenn Davis Army 792

2 Charles Trippi Georgia 435

3 Johnny Lujack Notre Dame 379

4 Doc Blanchard Army 267

5 Arnold Tucker Army 257

6 Herman Wedemeyer St. Mary's 101

7 Burr Baldwin UCLA 49

8 Bobby Layne Texas 45

By the time Davis had hung up his Army spikes he has posted some prodigious numbers:

RUSHING PASS RECEIVING SCORE

YEAR ATT YDS AVG NO YDS AVG TD TOTAL

1943 95 634 6.7 7 68 9.7 1 48

1944 58 667 *11.5 13 221 17 4 *120

1945 82 944 *11.5 5 213 42.6 0 108

1946 123 712 5.8 20 348 17.4 5 78

Totals 358 2957 8.3 45 850 18.9 10 354

* - Led the nation

In his 38 games for Army Davis had scored 59 touchdowns. Twenty-seven were over 37 yards, with his longest being 87.

The NFL's Detroit Lions drafted Davis, and both he and Blanchard had wanted to pursue pro football careers after graduating. But the Secretary of the Army refused to allow such activity, and the only football action the duo saw in 1947 was on the set of a low-budget film called The Spirit of West Point. The picture was hardly memorable, but it had its place in football history. During filming, Davis tore cartilage and ligaments in his right knee. They never healed properly.

Red Blaik had once commented about Davis that he was "as bashful as a girl on her first date, even though he is an All-America." That may have been true, but it did not stop the very eligible bachelor from being seen with a number of Hollywood's most attractive young starlets. Still in the Army, he dated Ann Blyth and after meeting Elizabeth Taylor at a touch football game on the beach (where else?), they became an item. Just before Davis shipped off for Korea, the couple became engaged ("When I saw that frank, wonderful face, I thought, 'This is the boy'"), but Taylor proved less reliable than Doc Blanchard and the engagement was off. He was later married briefly to actress Terry Moore before marrying the beautiful Ellen Harriet Lancaster Slack.

After completing his obligatory three-year Army hitch, Davis returned to football, signing with the Los Angeles Rams in 1950 and powering them to 9-3-0 record, good enough for a tie with George Halas's Chicago Bears. They defeated the Bears 24-14 but fell to the Browns in that year's Championship Game 30-28.

Davis had lead the Rams in rushing, scoring seven touchdowns, but thought the injury he had suffered during The Spirit of West Point's filming and the four-year layoff had taken their toll on his skills. "I was as good a player as a senior in high school," he once modestly said, "as I was with the Rams." After just one more season in the NFL he called it quits.

For three decades he worked as special events director for the Los Angeles Times, earning the respect of those around him. "West Point," said one sports writer a half-century ago, "might make an officer out of Glenn Davis, but he's already a gentleman."

Here is what was said at his passing

As most of you know, Glenn Davis - Army's fabled "Mr. Outside" -- recently passed away, and was buried adjacent to his revered coach, Red Blaik, at the West Point cemetery on March 18th. It was a bright day, with Glenn's widow, Yvonne, there as well as a number of the Davis family. Many of Glenn's teammates were there to bear witness, along with other friends and sports luminaries. Interestingly, Bobby Ross, and the entire West Point football coaching staff -- Every one of them -- were there, along with Joe Bellino, Navy's first Heisman award winner.

Pete Dawkins was asked to speak on behalf of the heritage of generations of the Army team.

Glenn Davis' Funeral

March 18, 2005

It goes without saying that Glenn was a remarkably gifted athlete, whose achievements stand tall in the annals of West Point, and in the history of sport in America. For that, he earned our undying respect, and deep admiration.

But, to me, Glenn was so much more, besides.

Over the past week, his passing caused me to think a lot about, "What makes a life?" - and, "Just what is it that made Glenn's life so memorable, and so special?"

I'm not at all sure that I've found the answer but, in my musings, three remembrances came to stand out, that I thought would be appropriate to share with you today.

First, it's important to remember that Glenn was not just a great star, he was also a great teammate. Even in the face of the torrent of notoriety - that, weekly, blustered with headlines bulging the wonder of his personal exploits (and often those of Doc Blanchard, "Mr. Inside", as well) Glenn thought of Steffy and Tucker and Poole and Foldberg .. and all the others, too. And he understood, without any question in his mind, that it was the team - not just the marvel of his personal performance - that brought victory, and truly deserved the accolade of success.

It wasn't forced, or false, or pretend, or clever, or calculated, or conscious, or contrived. It was Glenn. Given West Point, and the times, it seemed natural, and the right way to think - and behave. But in contrast with so many of our "sports-idols" of today, we can truly relish Glenn's dignity and quiet humility.

My second reflection is related, in that it was Glenn's humility that made his prodigious talent "human" - and accessible. During the season of 1946, I was 8 years old. Yet Glenn's impact on my life was very personal - and powerful. It wasn't just that he was a star. It wasn't just that he had "explosive" speed and uncanny balance. It was something more. Glenn had about him a grace... a kind of majesty. A personal aura that touched the spirit of a young 8-year old in Michigan. In a way that I can't fully explain, it was beguiling. Looking back, I realize that it kindled my youthful imagination, and sparked - for me - the allure of West Point, and the dream of the Army team.

Now, it occurs to me that there was a third distinctive attribute that Glenn shared with all of us who came to know him well: his friendship. I knew him for a little more than 40 years. Many of you here knew him quite a bit longer. The truth is, Glenn and I didn't see one another all that frequently. Most often, it was in conjunction with some sort of Heisman affair. But it was the kind of friendship where we picked up exactly where we had left off the last time, without missing a single beat.

In more recent times, after he and Yvonne were married, Judi and I -- and the two of them -- seemed to often find ourselves together at the end of the evening. I look back on those as treasured times. We talked, and laughed, and reminisced, and speculated on times ahead.

I always came away feeling refreshed. Glenn had a disarming directness, and selflessness about him that was very special. He never complained; instinctively dwelled on the positive half of everything; and came up with some of the most unexpected, and insightful, perspectives anyone could ever imagine.

It seems to me that there's little more you could ask for in a friendship than this.

Last fall, during half-time at the TCU game, a group of us were asked to assemble in Michie stadium, at the 50 yard line of Blaik field. As Glenn was feeling the difficulties of his therapy at that time, he slipped his arm into mine, and asked if I would escort him onto the field. On our way out, he began to apologize for needing my help. I interrupted him in mid-sentence and told him, "Listen to me: Glenn Davis never, ever needs to apologize to me." In fact, I told him that in all the years I had known him, and been with him - and, in fact, at that very moment - all my eyes ever saw was the strong, fresh, sculptured form of my boyhood idol.

What I said was the absolute truth. And I believe I saw him rise up a little more erect. And stride forward with strength and confidence.

"What is it that makes a good life?" He knew. And, in truth, that was the way he lived.

We miss you, Glenn. All of us do. But, more importantly, we will remember you -- long, and well.

Godspeed, good friend.

http://apse.dallasnews.com/contest/2004/writing/over250/over250_columns_first1.html

http://www.heisman.com/sports/m-footbl/spec-rel/031005aaa.html

http://archive.recordonline.com/archive/2004/11/19/losportm.htm

This writer believes West Point 1945 is the greatest team of all time. The 1944 Army team may actually deserve that title, but it was never tested. Army was also undefeated in 1946, 1948 and 1949.

Army's top stars during 1945-1949 were the effulgent "Touchdown Twins", Glenn Davis and "Doc" Blanchard, Arnold Tucker, Arnold Galiffa, "Rip" Rowan, Bobby Jack Stuart and Gil Stephenson in the back-field, and up front Joe Steffy, Art Gerometta, Jack Green, Bill Yoemans, Joe Henry "Tex" Coulter, Al Nemetz, and the sterling end duo of Hank Foldberg and Barney Poole.

In 1945 the Newspaper Enterprise Assoc. simply picked the entire Army team as its All-American team, stating no group of All-Americans could beat the Cadets.

Only a world war could have brought together such a collection of players to one institution. But it took the coaching genius of Col. Earl Blaik to mold the players into a cohesive unit.

In truth, Navy personnel was equal to Army's on an individual basis. The Middies never jelled as a team, however.

The 1951 Army outfit might have been as good as the 1945 Cadets, but the

infamous cribbing scandal wiped out the team.

General MacArthur stated it would take

General MacArthur stated it would take  28th Infantry Regiment

28th Infantry Regiment

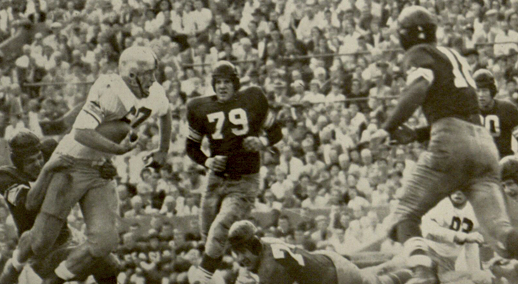

They played perhaps Army's Greatest Game.

They played perhaps Army's Greatest Game.

General MacArthur stated it would take

General MacArthur stated it would take

28th Infantry Regiment

28th Infantry Regiment  They played perhaps Army's Greatest Game.

They played perhaps Army's Greatest Game.

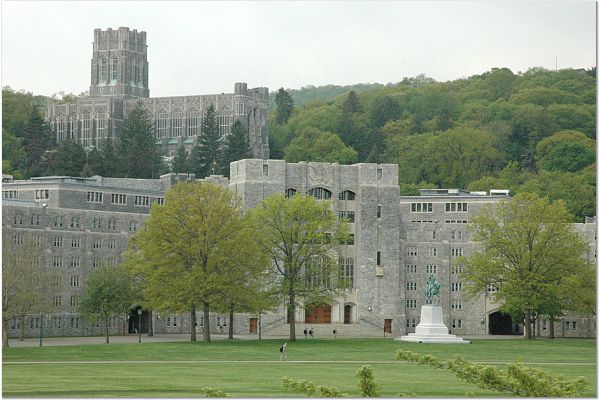

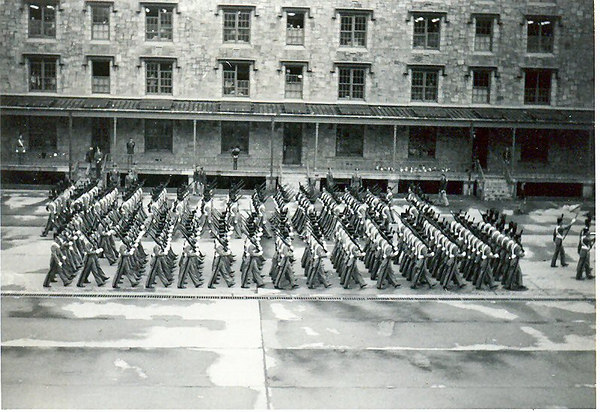

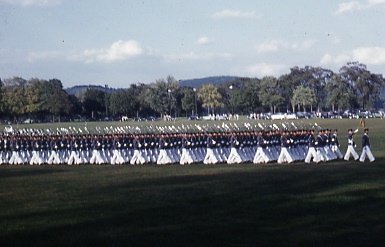

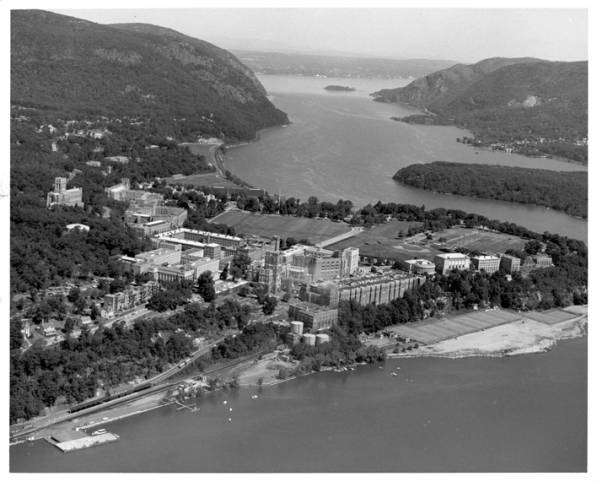

Cadet Barracks

Cadet Barracks