Duty Honor Country Speech

The recording of General of the Army Douglas MacArthur's Duty Honor Country Farewell on 12 May 1962 was accomplished only because Jim Ellis Class of 1962, Cadet Brigade Commander did not feel it was satisfactory to have only a written record.

Below the discussion of the events leading to the recording is a short discussion of the painting of the Pictorial of General MacArthur talking to us less than 4 weeks from Graduation. It is again provided by Jim Ellis.

The Farewell - (and I have never felt it was a speech - I always felt that he was talking to us - telling us what he expected from us, of me) is at the end of this page.

MacArthur's Farewell to the Corps

By Lieutenant General James R. Ellis, US Army (Retired)

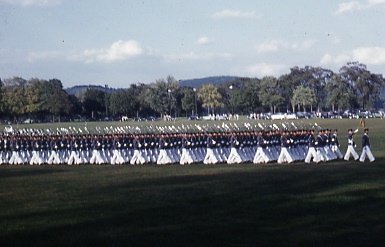

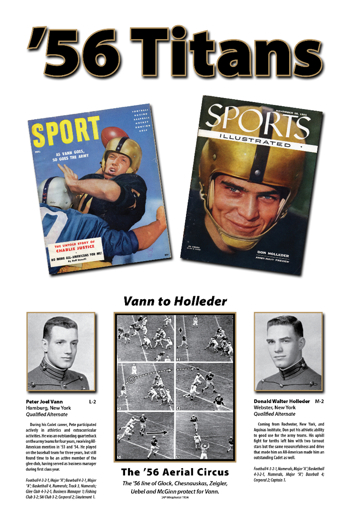

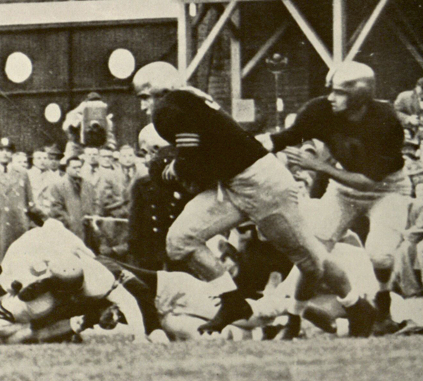

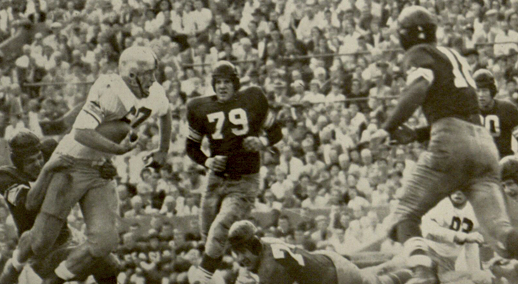

General Westmoreland and Jim Ellis Parading the Corps with the General.

Saturday, 12 May 1962

General of the Army Douglas MacArthur's trip to West Point had been well publicized and would be a major event. The afternoon before, I called the Academy Public Affairs Officer (PAO) - (an excellent officer with whom the Brigade Staff had a good working relationship), and I asked him about arrangements to record the General's speech. He said they did not do that - instead they would release a copy of the speaker's written remarks to the press after the event. This did not seem satisfactory. I asked my roommate, Pete Wuerpel, to see if he could do something so that at least he and I would have a recording of the speech. Pete was the Cadet Brigade Adjutant and used the dining hall public address system at every meal to make announcements. He borrowed a reel to reel recorder from a fellow cadet and made the connections.

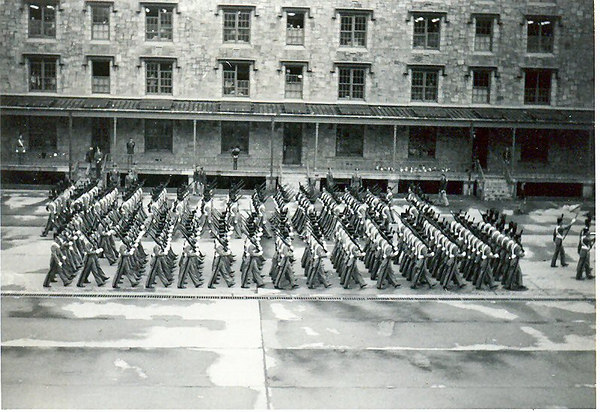

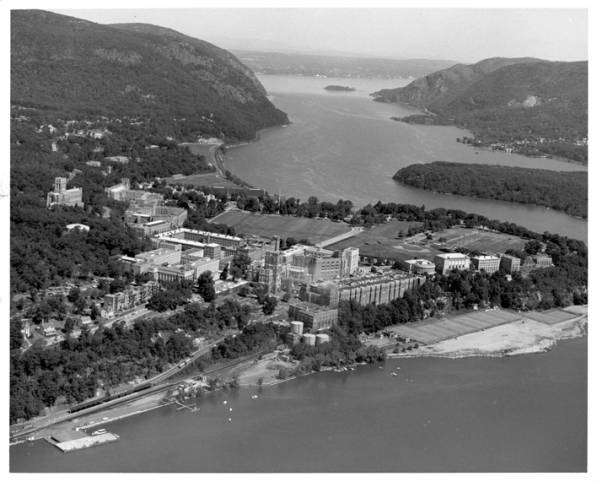

That Saturday was a perfect day - clear and sunny but not too hot. As you remember, the parade field was oriented differently than today with the reviewing stand directly across the street from the Superintendent's House. The dining hall had not been expanded and had not encroached on the parade field - consequently the field was larger than it is now. Spectators completely surrounded the field - the Academy civilian police (who worked with the MP's and were responsible for crowd control) estimated the number at 150,000. Remember, the Academy was wide open to the public at that time.

It was a full Brigade Parade. At the appropriate time the Thayer Award was presented to General MacArthur by the President of the Association of Graduates, Lieutenant General (Retired) Leslie Groves (who had directed the Manhattan Project in WWII). Following the presentation, Generals MacArthur and Westmoreland and I trooped the line in a jeep driven by the Supe's driver. A picture of the jeep moving in front of the Corps appeared on one of those two page displays in Life magazine following MacArthur's death in 1964.

After the parade, the Corps, Tac Officers, Instructors and invited guests moved into Washington Hall. Generals MacArthur, Westmoreland and Groves took their places on the dais which had been set up just inside the main door. Glen Blumhardt, Cadet 1st Regimental Commander, escorted Mrs. MacArthur and Mrs. Westmoreland to a table on the Poop Deck.

My table was immediately in front of the dais. Cadet tables held 10 people. As Brigade Commander I was table-com hosting nine active duty and retired 4 Star Generals - minding my manners with every bite!

Following lunch, General MacArthur gave that great Duty, Honor, Country speech. I'm sure you have heard it many times. He had no notes except one 3 x 5 card with one word on it - "doorman" -you have heard the joke. The occasional 'klunk' on the audio is the sound of the General's ring hitting the wooden podium as he shifted his grip. When he finished he turned around and saluted his wife on the Poop Deck. At the end there were no dry eyes on my table.

After the official party left, Wuerpel and I were changing in our room (8 1/2 - Division which no longer exists), we both had dates waiting--(I married mine 7 weeks later - we celebrate our 45th this summer). Pete had recovered the recorder.

The phone rang:

PAO (in a panic), "The General had no written text and the press is going crazy for a copy of the speech - someone told me you made a recording."

Ellis, "Yes sir, it is here on the table".

PAO, "My minion will be there shortly to pick it up."

(Interesting title for the Captain who rushed in 10 minutes later and ran out with the tape). The PAO took it to the Foreign Language lab and made multiple copies. A secretary worked all afternoon transcribing the speech to hard copy to release to the press. Pete retrieved the original tape and, to the best of my knowledge, still has it.

The Supe sent two of the written copies to General MacArthur - MacArthur signed both and sent them back. General Westmoreland kept one and gave the other to me. Seth Hudgins told me a few months ago that, over time, MacArthur signed several more.

12 May 1987 - The Twenty-Fifth Anniversary:

The Academy held a ceremony to mark the 25th Anniversary of the Duty Honor Country speech.

LTG Dave Palmer was Supe and invited me to attend - I was an Assistant Division Commander of the 10th Mountain Division at Ft. Drum. Mrs. MacArthur was the honored guest. General (Ret.) and Mrs. Stilwell came - Stilwell had been Commandant in 1962. And, there were several of MacArthur's wartime comrades present. General and Mrs. Westmoreland were unable to attend.

While there, Mrs. MacArthur mentioned that the General had rehearsed the speech 3 or more times to her. Though he spoke without notes, he was well rehearsed.

Pictures and film clips of General MacArthur's life were super-imposed over the audio and the resulting video was shown to the entire Corps in Eisenhower Hall as part of the ceremony. I'm sure you have seen it.

For the MacArthur Speech, click this link:

http://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/douglasmacarthurthayeraward.html

(Audio mp3 of Address)

Jim Ellis has pointed out that entering Duty Honor Country in search engines will turn up other sources on MacArthur and his speech

Bob Carroll has added that he was able to "burn a copy on a Disc by doing the following:

go to AmericanRhetoric.com

search for DHC speech (can do it by decade)

scroll down to mp3 format and copy onto your computer

then burn it.

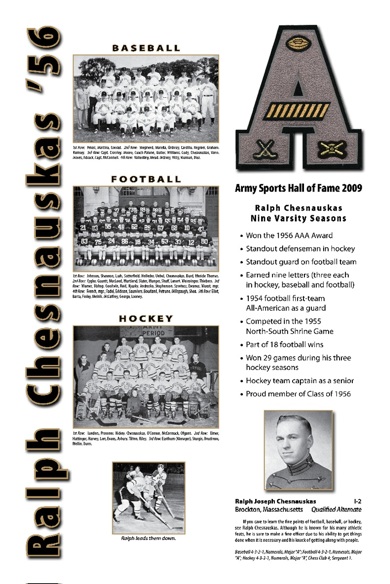

The Pictorial

The artist painted 4 Cadets from the Class of '62 onto MacArthur's Duty Honor Country. The 4 faces are from a photo taken at MacArthur's penthouse apartment in NYC on the occasion of MacArthur's 82d birthday (26 Jan '62). The four cadets were George Kirschenbauer (who was on a baseball trip in May of 62 when MacArthur gave the talk), "Mike Grebe", Glen Blumhardt, and Jim Ellis. Blumhardt is the guy in the lower left corner of the painting. Ellis is pretty clear in the middle. George is easy to pick out but "Mike Grebe" is harder to identify.

The artist (Paul Stucke) worked full time for FAA in DC and was hired by Lew Iwlew of Vladimir Arts to paint the event. Paul and I conferred several times on the setting and I provided him a copy of the photo so he could see cadet uniforms and have a profile shot of MacArthur as he looked at that time. Paul's career as an artist took off as a result of this work; so, he retired from the FAA, moved to Seattle and works full time as an artist.

The Class of '63 bought 518 copies of the print (for about $140 each). They then had each copy signed by 5 people (Bob Hope, Jim Ellis, Colin Powell, Norman Schwarzkopf, and "William Westmoreland"). They sold each print for $700 as a way of raising money for their class gift to West Point. This initiative was orchestrated by Lynn Cook who is the President of that Class.

General MacArthur - 12 May 1962

General Westmoreland, General Grove, distinguished guests, and gentlemen of the Corps!

As I was leaving the hotel this morning, a doorman asked me, "Where are you bound for, General?" And when I replied, "West Point," he remarked, "Beautiful place. Have you ever been there before?"

No human being could fail to be deeply moved by such a tribute as this [Thayer Award]. Coming from a profession I have served so long, and a people I have loved so well, it fills me with an emotion I cannot express. But this award is not intended primarily to honor a personality, but to symbolize a great moral code - - the code of conduct and chivalry of those who guard this beloved land of culture and ancient descent. That is the animation of this medallion. For all eyes and for all time, it is an expression of the ethics of the American soldier. That I should be integrated in this way with so noble an ideal arouses a sense of pride and yet of humility which will be with me always: Duty, Honor, Country.

Those three hallowed words reverently dictate what you ought to be, what you can be, what you will be. They are your rallying points: to build courage when courage seems to fail; to regain faith when there seems to be little cause for faith; to create hope when hope becomes forlorn.

Unhappily, I possess neither that eloquence of diction, that poetry of imagination, nor that brilliance of metaphor to tell you all that they mean. The unbelievers will say they are but words, but a slogan, but a flamboyant phrase. Every pedant, every demagogue, every cynic, every hypocrite, every troublemaker, and I am sorry to say, some others of an entirely different character, will try to downgrade them even to the extent of mockery and ridicule.

But these are some of the things they do. They build your basic character. They mold you for your future roles as the custodians of the nation's defense. They make you strong enough to know when you are weak, and brave enough to face yourself when you are afraid. They teach you to be proud and unbending in honest failure, but humble and gentle in success; not to substitute words for actions, not to seek the path of comfort, but to face the stress and spur of difficulty and challenge; to learn to stand up in the storm but to have compassion on those who fall; to master yourself before you seek to master others; to have a heart that is clean, a goal that is high; to learn to laugh, yet never forget how to weep; to reach into the future yet never neglect the past; to be serious yet never to take yourself too seriously; to be modest so that you will remember the simplicity of true greatness, the open mind of true wisdom, the meekness of true strength.

They give you a temper of the will, a quality of the imagination, a vigor of the emotions, a freshness of the deep springs of life, a temperamental predominance of courage over timidity, of an appetite for adventure over love of ease. They create in your heart the sense of wonder, the unfailing hope of what next, and the joy and inspiration of life. They teach you in this way to be an officer and a gentleman.

And what sort of soldiers are those you are to lead? Are they reliable? Are they brave? Are they capable of victory? Their story is known to all of you. It is the story of the American man at arms. My estimate of him was formed on the battlefield many, many years ago, and has never changed. I regarded him then as I regard him now as one of the world's noblest figures, not only as one of the finest military characters, but also as one of the most stainless. His name and fame are the birthright of every American citizen. In his youth and strength, his love and loyalty, he gave all that mortality can give.

He needs no eulogy from me or from any other man. He has written his own history and written it in red on his enemy's breast. But when I think of his patience under adversity, of his courage under fire, and of his modesty in victory, I am filled with an emotion of admiration I cannot put into words. He belongs to history as furnishing one of the greatest examples of successful patriotism. He belongs to posterity as the instructor of future generations in the principles of liberty and freedom. He belongs to the present, to us, by his virtues and by his achievements. In 20 campaigns, on a hundred battlefields, around a thousand campfires, I have witnessed that enduring fortitude, that patriotic self abnegation, and that invincible determination which have carved his statue in the hearts of his people. From one end of the world to the other he has drained deep the chalice of courage.

As I listened to those songs (of the glee club), in memory's eye I could see those staggering columns of the First World War, bending under soggy packs, on many a weary march from dripping dusk to drizzling dawn, slogging ankle deep through the mire of shell shocked roads, to form grimly for the attack, blue lipped, covered with sludge and mud, chilled by the wind and rain, driving home to their objective, and for many, to the judgment seat of God.

I do not know the dignity of their birth, but I do know the glory of their death. They died unquestioning, uncomplaining, with faith in their hearts, and on their lips the hope that we would go on to victory. Always, for them: Duty, Honor, Country; always their blood and sweat and tears, as we sought the way and the light and the truth.

And 20 years after, on the other side of the globe, again the filth of murky foxholes, the stench of ghostly trenches, the slime of dripping dugouts; those boiling suns of relentless heat, those torrential rains of devastating storms; the loneliness and utter desolation of jungle trails; the bitterness of long separation from those they loved and cherished; the deadly pestilence of tropical disease; the horror of stricken areas of war; their resolute and determined defense, their swift and sure attack, their indomitable purpose, their complete and decisive victory - - always victory. Always through the bloody haze of their last reverberating shot, the vision of gaunt, ghastly men reverently following your password of: Duty, Honor, Country.

The code which those words perpetuate embraces the highest moral laws and will stand the test of any ethics or philosophies ever promulgated for the uplift of mankind. Its requirements are for the things that are right, and its restraints are from the things that are wrong.

The soldier, above all other men, is required to practice the greatest act of religious training - sacrifice.

In battle and in the face of danger and death, he discloses those divine attributes which his Maker gave when he created man in his own image. No physical courage and no brute instinct can take the place of the Divine help which alone can sustain him.

However horrible the incidents of war may be, the soldier who is called upon to offer and to give his life for his country is the noblest development of mankind.

You now face a new world - a world of change. The thrust into outer space of the satellite, spheres, and missiles mark the beginning of another epoch in the long story of mankind. In the five or more billions of years the scientists tell us it has taken to form the earth, in the three or more billion years of development of the human race, there has never been a more abrupt or staggering evolution. We deal now not with things of this world alone, but with the illimitable distances and as yet unfathomed mysteries of the universe. We are reaching out for a new and boundless frontier.

We speak in strange terms: of harnessing the cosmic energy; of making winds and tides work for us; of creating unheard synthetic materials to supplement or even replace our old standard basics; to purify sea water for our drink; of mining ocean floors for new fields of wealth and food; of disease preventatives to expand life into the hundreds of years; of controlling the weather for a more equitable distribution of heat and cold, of rain and shine; of space ships to the moon; of the primary target in war, no longer limited to the armed forces of an enemy, but instead to include his civil populations; of ultimate conflict between a united human race and the sinister forces of some other planetary galaxy; of such dreams and fantasies as to make life the most exciting of all time.

And through all this welter of change and development, your mission remains fixed, determined, inviolable: it is to win our wars.

Everything else in your professional career is but corollary to this vital dedication. All other public purposes, all other public projects, all other public needs, great or small, will find others for their accomplishment. But you are the ones who are trained to fight. Yours is the profession of arms, the will to win, the sure knowledge that in war there is no substitute for victory; that if you lose, the nation will be destroyed; that the very obsession of your public service must be: Duty, Honor, Country.

Others will debate the controversial issues, national and international, which divide men's minds; but serene, calm, aloof, you stand as the Nation's war guardian, as its lifeguard from the raging tides of international conflict, as its gladiator in the arena of battle.

For a century and a half you have defended, guarded, and protected its hallowed traditions of liberty and freedom, of right and justice.

Let civilian voices argue the merits or demerits of our processes of government; whether our strength is being sapped by deficit financing, indulged in too long, by federal paternalism grown too mighty, by power groups grown too arrogant, by politics grown too corrupt, by crime grown too rampant, by morals grown too low, by taxes grown too high, by extremists grown too violent; whether our personal liberties are as thorough and complete as they should be. These great national problems are not for your professional participation or military solution. Your guidepost stands out like a ten-fold beacon in the night: Duty, Honor, Country.

You are the leaven which binds together the entire fabric of our national system of defense. From your ranks come the great captains who hold the nation's destiny in their hands the moment the war tocsin sounds. The Long Gray Line has never failed us. Were you to do so, a million ghosts in olive drab, in brown khaki, in blue and gray, would rise from their white crosses thundering those magic words: Duty, Honor, Country.

This does not mean that you are war mongers.

On the contrary, the soldier, above all other people, prays for peace, for he must suffer and bear the deepest wounds and scars of war.

But always in our ears ring the ominous words of Plato, that wisest of all philosophers: "Only the dead have seen the end of war."

The shadows are lengthening for me. The twilight is here. My days of old have vanished, tone and tint. They have gone glimmering through the dreams of things that were. Their memory is one of wondrous beauty, watered by tears, and coaxed and caressed by the smiles of yesterday. I listen vainly, but with thirsty ears, for the witching melody of faint bugles blowing reveille, of far drums beating the long roll. In my dreams I hear again the crash of guns, the rattle of musketry, the strange, mournful mutter of the battlefield.

But in the evening of my memory, always I come back to West Point. Always there echoes and re-echoes: Duty, Honor, Country.

Today marks my final roll call with you, but I want you to know that when I cross the river my last conscious thoughts will be of The Corps, and The Corps, and The Corps.

I bid you farewell.

What we remember of that day in May when he talked to us

This Saturday, 12 May 2007, marks the 45th Anniversary of the presentation of the Thayer Award to General of the Army Douglas MacArthur '03 and his legendary Duty, Honor, Country acceptance speech, and several graduates have shared their memories of that day. Perhaps the most significant recollection is of the absolute silence of the Corps and other attendees during the speech.

"Larry Waters" '62 added that he had never seen the Corps standing so tall on The Plain as when the general trooped the line during the review that preceded the speech.

"Dennis Bennett" '62 noted that "you could hear a pin drop" until a man began taking photographs using a camera with a noisy shutter. A general officer sitting nearby reached over to the man, gently touched his hand, and put a finger up to his lips to indicate silence was requested. All this was done without taking his eyes off GEN MacArthur for more than a few seconds.

"Bob Mecada" '62 also recalled the silence during the speech but added that the mess hall was silent for at least 15-20 seconds afterwards as well, the effect of the speech was that dramatic. Then the attendees began to applaud.

"Pat Canary" notes that when Jim Ellis '62 dismissed the Corps, the silence resumed as the cadets left the mess hall and returned to the barracks. Many seemed to appreciate the fact that the speech was GEN MacArthur's farewell to West Point.

Perhaps the most comprehensive recollection was provided by "Dick Chegar" '62, who served as escort for GEN Anthony McAuliffe '19 of Bastogne fame. He recalls that Mrs. MacArthur, Mrs. Westmoreland, and their escorts were seated on the poop deck while a number of famous general officers were seated at ten-man tables near the podium on the ground floor. GEN MacArthur was 82 at the time, and this alone caused a sense of drama in the air, almost symbolic of the passing of an era. His opening joke about the doorman at his hotel asking if he had ever been to West Point before caused the mess hall to erupt in laughter, but the mood soon grew serious as MacArthur spoke of distant battlefields and the American soldier's "patience under adversity, courage under fire, and modesty in victory." He delivered his speech without notes, and most attendees were acutely aware of his exemplary oratory. About two-thirds of the way through the speech, however, MacArthur hesitated for a moment, turned to his right, and looked directly at his wife Jean. It was as if a ray of light passed between them in that moment. GEN MacArthur then flawlessly continued his speech to completion. Several weeks later, the Cadet First Captain visited GEN MacArthur in New York City and was told that the speech had been written in advance, committed to memory and rehearsed several times. Dick felt that the pause occurred because the next line may have been forgotten for a moment. Many years later, when one of Dick's captains won the annual General Douglas MacArthur Leadership Award, Dick told him the story about the momentary pause. When the captain later met Mrs. MacArthur at the ceremony, she confirmed her recollection of the glance that passed between them on that day.

"John Goodwin" '62 was a member of the cadet officer honor guard arrayed on the steps of Washington Hall. He recalls that GEN MacArthur was extremely gracious, stopping to talk and shaking hands with a strong grip.

"Fred Gorden" '62, also in the honor guard on the steps, recalls an air of excitement because MacArthur was already a legend at West Point. At the top of the steps, the general turned and said, "I thank you all."

"Neil Nydegger" '62 was impressed by the General's "sincerity and genuine commitment to the Army and to West Point" and how he had "captured the simple essence of being a soldier."

"Gary Sharp" '62 recalled: -- "MacArthur's well-chosen words and deliberate delivery made an emotional impression on me that I will never forget ... being the first in war and possibly the first to die, the loneliness of remote duty, the hardships on a soldier's family, the fears that all soldiers face in battle, the camaraderie soldiers experience, the pride and honor felt when a soldier's job has been done well, and the deeply emotional sound of Taps at a soldier's burial ... were all in his speech. If they were not in his exact words, they were in the silences between them. If any soldier ever needs encouragement before or in battle, he only needs to hear or read MacArthur's words."

"Fred Bothwell" '62, first in his class in English, was impressed with the general's choice of words like "tocsin" and "mournful murmur of the battlefield," calling his speech "the most brilliant piece of oratory that I have ever heard."

Stu Sherard '62 was moved by the reaction of his roommate, Frank Reasoner, a former Marine sergeant who returned to the Marine Corps after graduation and was killed in action on 12 July 1965 in Viet Nam, receiving the Medal of Honor posthumously. Hard core Marine Reasoner had tears in his eyes several times during the speech.

John Dilley'62 also recalls that "there was not a dry eye in the house," but his strongest recollection is of MacArthur's intoning, "... the Corps, and the Corps, and the Corps."

"Bob Reid" '62 had a similar recollection of being touched deeply and moved to tears, especially by MacArthur's final allusion to "the Corps."

Forty-five years later, "Bob Cooper" '62 still finds himself quoting MacArthur's speech to those he meets who are opposed to the war in Iraq: "This does not mean that you are warmongers. On the contrary, the soldier, above all other people, prays for peace, for he must suffer and bear the deepest wounds and scars of war."

"Bill Ross" '62 recalled MacArthur's sonorous delivery and a more pragmatic aspect: GEN MacArthur, as a former Superintendent, exercised the prerogative normally reserved to heads of state and granted amnesty, permitting Bill to enjoy the beautiful Saturday afternoon without sitting confinement.

John Taylor '62 recalls that Army's newly-established Rugby Team, of which he was one of the co-founders, went on that afternoon to beat the leading rugby club in the nation, the New York Rugby Club.

"Mike Moore" '62 recalls being photographed presenting a 1962 Howitzer to the general (Mike was the editor) and then flying off to Syracuse to play lacrosse, Army winning by about ten points.

Gus Fishburne '62 recalls that the baseball and lacrosse teams attended in uniform, standing along the walls of the north wing during the speech.

Tom Eccleston '62 recalls a very personal and pragmatic result of having heard the speech. After several years of active duty and a tour in Viet Nam, Tom embarked upon a civilian career selling high voltage equipment and was given The Boston Edison Company as a challenge. While attempting to sell some old timers at Boston Edison his company's equipment, he happened to mention that he had heard MacArthur's speech. He was then seen as a minor celebrity and received a large contract within the year.

Like many of his classmates, "Dave Francis" '62 initially was waiting impatiently for lunch to be over so that he could hop into his Austin Healey sports car and drive down to Philadelphia for the weekend: "in the subsequent years, the memory of that weekend in Philadelphia has faded, but the memory of MacArthur's speech has remained with me."

Denny Coll '65, however, was just a Plebe at the time and a member of the football team brought back in uniform and pads from spring practice to hear the speech. He also was a sleep-deprived Plebe who had just had a hearty football training table meal in a very warm, un-air conditioned mess hall. He and some classmates dozed off after the opening minutes of the speech, only to be awakened by the sound of MacArthur's West Point ring inadvertently striking the podium near the microphone. His recollection of the speech is limited to its moving conclusion: "Today marks my final roll call with you, but I want you to know that when I cross the river my last conscious thoughts will be of The Corps, and The Corps, and The Corps. I bid you farewell." He then realized that he was a part of history but had missed most of a historic speech.

"Ed Hamilton" '62 I was on the track tables back in the Corps Squad area during the speech. I recall that as the General began to speak, his voice sounded a little weak and there was some minor snickering and rustling among the athletes, but it didn't take more than a few seconds for that to stop as all of us started to realize that we were witnesses to history in the making.

"Will Cannon" To me, one of the coolest things about that day, was this: For some reason unknown to me at the time or since, I was selected to sit down front with a table of VIPs. I couldn't have been more than 20 feet away from him. As he reached the part near the end that goes "The shadows are lengthening for me . . ., we all began to realize that he knew he was going to die soon and would never be back. Then, when he said ". . .my last conscious thoughts will be of" (His wife? -- No!); (His son? No!); (His distinguished career in the United States Army? --No!) "The Corps, and The Corps, and The Corps." Then when he delivered the final line, "I bid you farewell", he kind of turned a little to his left and looked up to the Poopdeck where his wife was watching with tears on her cheeks, and he gave her the slightest little wave, which she returned, as if to say, "Well done". I was embarrassed that I was crying like a baby, then I looked toward the head of the table, and there sat a 4 Star General, crying like a baby.

Others also missed the speech, but for official reasons. Ernest Gus Zenker '62 had branched Air Defense Artillery and was visiting a Nike missile site in New Jersey that Saturday, along with several Air Defense classmates.

Many more would have missed hearing the speech, however, had it not been for the presence of mind of the First Captain, Jim Ellis. The previous evening he had contacted the Public Information Officer at the time and asked if the speech would be recorded. The PIO office had no plans to do so. Jim then asked his roommate, Pete Wuerpel, the Adjutant, to set up a recorder on the poop deck. All other recordings of the speech owe their genesis to Pete's reel-to-reel tape .. which he still has. And now you know why we have it today.

|

General MacArthur stated it would take

General MacArthur stated it would take  28th Infantry Regiment

28th Infantry Regiment

They played perhaps Army's Greatest Game.

They played perhaps Army's Greatest Game.

General MacArthur stated it would take

General MacArthur stated it would take

They played perhaps Army's Greatest Game.

They played perhaps Army's Greatest Game.

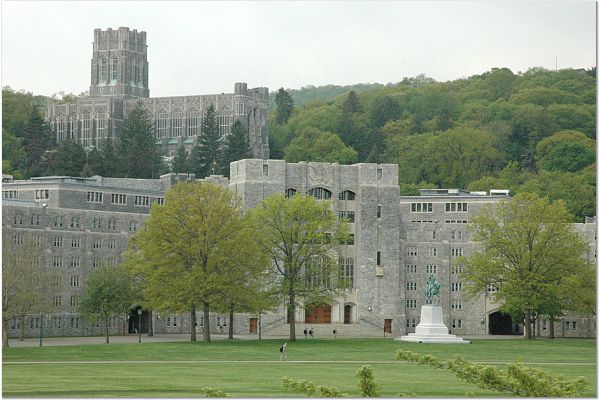

Cadet Barracks

Cadet Barracks